Thoughts from the Steppes of Central Asia

distance: 2357.40km

duration: 91h 49min

Amritsar and from Mumbai to the northern Western Ghats

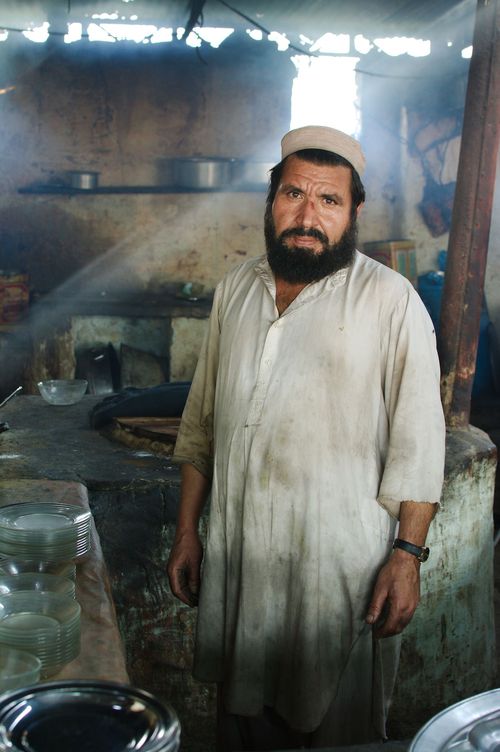

Amritsar is another shabby town along the Grand Trunk Road. Its dominating building type is the rectilinear concrete box - unsightly, narrow dark-grey blocks, 2-4 storeys high, whose very composition gives away how they where poured in a haste with the cheapest materials available. Rebars are left to protrude from the flat-roofs, so annexe and additional floors can be easily fused with the older part of the building. No person with a fondness of aesthetic appeal has ever reviewed the plans (Though i doubt there actually are "plans", the building works are done ad-hoc i guess). The owners of these buildings seem to aim for only one purpose when they commission the construction - creating a physical barrier to protect from the elements, as economical as possible.

To improve things not a bit, the street facing sides of these dwellings are literally plastered by a cacophony of signs promoting businesses large and small. These panels feature all types of font-styles, colors and sizes, sometimes with pixelated images indicating the kind of business they promote - at night they are of course accentuated by blaring neon and fluorescent lights.

So while the vertical dimension of Amritsar's streets is utterly disfigured by this incoherent, cluttered medley, the horizontal plane is dominated by heavy, incessantly hooting traffic and where there is rare dedicated space for pedestrians in the form of a sidewalk, it is disconnected and you will rarely find more than 2 meters where you don't have to step over open sewers and other holes and gaps, step down and up or avoid poles which have been planted in the middle of the path. There is no careless strolling in the cities of the east, you have to watch your step every step.

The indian subcontinent is strewn with this kind of ugly small to medium size cities (As is much of the rest of Asia, it starts in Turkey). Whenever we ride into these agglomerations after a few days in the countryside, i'm astonished and marvel how the population can put up with this - just the stress induced from the noise must shorten their lifes by years!

I always imagine how interesting it would be to put a resident of such a place into the centre of an old european city and study their reaction. They would be astonished how neat and well ordered a city can be, how quiet the traffic is in comparison. It must be fascinating to see their facial expression, the alternation of confusion and excitement. But i also imagine many Indians would feel that european cities are sterile and frigid, which they are, compared to the liveliness of asian street life.

There are of course plenty of ugly corners in european cities, especially at the fringes and near main roads. Nobody wants to live there, so the rents are low and attractive enough for poor immigrants and low income households (Which in turn makes these areas even less attractive for development and business investments).

Additionally many towns wear the stigma of the Second World War (Especially in Germany), when large parts of the historic fabric of numerous major cities where carpet bombed to rubble by the Royal Air Force. In the economic boom after the war, the cities where rebuilt in a functional, modernist and most of all cheap fashion (Not too far from the style mentioned above), the historic appearance of the streets was rarely reconstructed except for siginificant landmarks like cathedrals. This is a liability that will haunt Germany for generations.

Still you would have to look at the worst corners of an european city that are as rundown and messy as a typical street in an Indian city.

In general the majority of European urban development is well planned, organized and neat, while the majority of Indian (and Asian) urban development is not.

The same can be applied to a wide field of technological and organizational differences. Europe (And deductively North America as Europe's cultural heir) has the edge on most of them!

Since we have been cycling through Central Asia i have marveled about the various reasons why we in Europe are so advanced while other regions of the world can't seem to catch up.

The gap in wealth and advance hasn't always been this large.

My great-aunt (My grandmother's sister) lived in a tiny farmhouse in a rural region of Styria/Austria until she died of old age in the 1990s. She never had running water or electricity. She cooked with wood, washed her clothes by hand and lived from her homestead. Her life until her death was not different than a rural life today in India.

Like her, my grandmother had grown up on a farm in the 1920s to 1940s - work was done by hand or with the help of horses and cows. It was hard manual labour, there where no machines, electrification, centralized plumbing and a sewage system didn't not exist.

The film "The White Ribbon" by Michael Haneke vividly depicts this kind of rural life in Europe in the early 20th century (If you haven't seen the film, you should!).

224 years ago, India's was producing 24.5% of the world's manufactured goods (Britain 1.9%), a number which dropped to 1.7% by the end of the 1800s - the Industrial Revolution had allowed nations like Britain and the U.S. to increase their productive output manifold (And also by exploiting a cheap and powerless workforce).

But the advances of technology where not confined to the Anglo-Saxon Countries forever and during the Raj the British invested heavily in the Indian infrastructure, railways and telegraph lines where built early on and by the end of the 19th century, the fourth-largest railway network in the world had been established on the Indian Subcontinent.

Today the gap between developed and developing countries is huge compared to just 100 years ago. (There's also a huge gap between the lower and the middle class in India - and it's pretty palpable to a visitor of the country).

Cycling through the countryside the difference in wealth and technological advance is apparent by simple things in the daily life.

Washing of clothes is done by hand, usually in a river or pond near the village. Water still has to be carried in typical metal- or plastic vessels from the village well to the home - or there is a large tank on the roof which is filled by a pump from a well in the backyard (But that's probably already something only the middle class can afford).

A sewage system is something unheard of outside of major towns, wastewater treatment does not seem to exist anywhere. The power-grid is ancient and blackouts happen daily. Organized collection and ecological disposal of rubbish in treatment facilities? - of course not! Rubbish accumulates in some corner until someone burns it - or not.

In Europe all of the aforementioned things are mechanized (Washing machines!) and infrastructure works and is planned and operated to perfection.

The people in developing countries find creative solutions though and labour is cheap - we've seen human-powered recycling of cardboard and plastic bottles. Repairment/recycling of defective appliances/machines is much more common (In Austria you'll most likely have to throw away and replace it with something new if you don't have the skill to fix it yourself, repairing is mostly far too expensive).

While cycling through these regions we've also found that regulation and laws in Europe seem to work a lot better and are executed more effectively.

As an example, in Austria you are not allowed to build your house however you please - it has to fit certain standards, technically and aesthetically, if you drive like a maniac you will eventually get a ticket or loose your license, your vehicle has to meet high ecology and security standards and pedestrians have the right of way in most traffic situations.

There might be a thicket of regulations in Central Asia and India (We've experienced plenty of bureaucracy ourselves), but laws don't appear to have any effect (Traffic is nuts and i've described the rank growth of buildings in the beginning). Probably that's because you can bribe yourself out of any restrictions and norms?!

There's virtually no corruption in developed countries on the citizen level in dealing with public authorities (There's plenty of corruption on a higher-level though).

I have never in my life paid a bribe to an official in Austria to get the administration to do something - a majority of Indian's have first hand experience of paying bribes or influence peddling (But Central Asia is a lot worse in this regard, we have seen bribes changing hands in front of our eyes in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. We ourselves have been able to avoid bribing anyone during this travel).

I've been hoping to understand at some point why the living situation in developing countries is still so bad, after all, the opportunities are not extremely out of favor and the initial situation was not so much different just a century ago. And one can hardly blame it on aftereffects of colonialism or economic discrimination by the developed nations alone.

One of my reasonings for the advance which i turned over and over in my head was based on the elaborateness and cross-linkedness of society in developed nations. The education is top-notch, literacy is near 100% and you have specialists for everything.

Knowledge in all fields has been built up for decades, if not centuries, there is continuous improvement in most fields and the best ways are constantly worked out. On all layers of society you have people with expertise and the application of their knowledge leads to an intertwined economy that works on a high level of efficiency.

(I make it sound like there's absolute perfection in my home country, which of course is not the case, especially in regards to future questions of societal development. Infrastructure for and administration of daily life is pretty good though where i come from).

In comparison a country like Tajikistan has a much harder time to run it's business. You are lacking key personalities in all layers of society, because the education level is still to low. The state budget is limited, as the income from taxes is minimal. The infrastructure lacks on all ends - the few roads you have are bad, the train network is weak, you have a few power plants which are hopelessly overburdened and can't provide the weakling industry, public health is close to non-existant. Your administrative organization is corrupt on all levels and you can do little about it, as your budget does not allow for higher wages.

How do you kickstart such a country?

On top of it all, the government has the short-sighted desire to reign authoritarian and continue the ways they got used to in the positions the same people held when they where still part of the Soviet Union.

This was in essence my hypothesis on the issues of the Central Asian Republics. I have no inkling in the field of development of nations but i still find my explanation convincing and i hope it's at least partly true for the case of Central Asia.

When i finally saw the chance to write my thoughts down in this essay 4 days ago, i was going to have to apply my Central Asia ideas to India, which has a much different background and environment than Central Asia.

After several approaches to formulate my thoughts in this blog and lots of research, i realized the circumstances where much different and the reasoning above can't explain the complex issues on the Indian Subcontinent. It's obvious on first sight that Pakistan and India are in a much better shape than the likes of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. There is plenty of potential for development and there are much more resources available.

India has in the decades since it's independence been hampered by corruption, a soviet-style planned economy and the License Raj, a state enforced policy of licensing and regulating the planned economy which led to slow economical growth compared to other Asian countries like South Korea and Malaysia, whose growth rates where much higher between 1950 and 1990. The economy was only liberated in 1991 and since then India has grown much faster.

This appears to be an important aspect of why India's progress has been so slow in the 20th century. It would be an fascinating thought-experiment to see where India would stand today if there hadn't been 50 years of socialism and government owned economy.

During my research i realized however, it would take the time and length of a dissertation to properly analyze what i've been attempting to do in a single blog post.

What i can safely state though is that India, despite it's growth and fresh hope in a new administration has a long way to go. There is so much to clean up and improve, a large part of its huge population lacks education but is within reach to achieve enough wealth to take part in consumerism, which will lead to even more environmental and structural problems.

I wonder how India's cities will look like 30 years from now. Just like the purely functional post-war reconstructions in Europe, the undamped building and urban sprawl will cause plenty of headaches for future generations.

Note: I'm leading the argument for rationally established entities only - namely infrastructure, administration, legislation, etc., and i'm aware that my viewpoint and judgement is largely influenced by a "western" cultural hegemony. I can't read people's mind - i can hardly communicate with most Indians to hear their opinion! - and i concede there are different viewpoints and influences where efficiency and success are not means to an end (Religion, Spritiuality, alternative society models), so my judgement is subjective and must not offend anyone.

This essay solely tries to boil down past discussions on our experiences of the regular, daily life of cycling and living in Central Asia and the Indian Subcontinent and to attempt to answer the questions of why things are the way they are. I'm merely arguing practical, material, organizational issues where we know it could be done better and which affect the locals just as much, however placid they may take it - so i don't intend to get to philosophical or ideological about it.

On the Grand Trunk Road - Islamabad to Lahore

distance: 396.77km

duration: 47h 52min

Islamabad is probably the most tranquil inhabitated place in South Asia. Beeing a planned city, it's layout is a grid of several residential quarters with a marketplace in the center. The whole city appears to be a huge park - it's very green and the wide avenues easily accomodate the traffic.

It's not good place to be a pedestrian though as it simply is too far spread out, and even with our bicycles we rarely went further than the adjoining quarters.

For two weeks we lived a plush live in Pakistan's capital city. Our warmshower-hosts villa provided all modern comfort and a very gentle housekeeper cooked for us daily. Despite all the comfort it was queer how every house has a high fence (Often with barbed wire on top) and a security guard in front of it. It also felt quite colonial to ask someone to prepare food for us and be treated deferent in restaurants and shops - as if we where some kind of superior beeings.

Daniela had catched a severe flu and spent the first week in bed, while i started working on our visa-application for India. India's embassy is located in the diplomatic enclave, a locked down part of Islamabad with high security measures and even higher fences. Going there personally turned out to be futile though - contrary to what the embassies website said, visa applications where only accepted when sent with a courier service (And when i went to the courier-service later, i learned there are two application forms and i of course had filled out the wrong one).

We visited the diplomatic enclave again a few days later with our host to show us the British High Commission. He was working for the british government and they had issued him with an armored Toyota Land-Cruiser - the standard model is already a huge vehicle - but with 4cm thick windows and steel plating, the armored version weighs more than 4 tons, a tank of a car!

Our host chuckled and shrugged his shoulders about the security measures they had set up for him and he found it amusing to show us a glimpse of the life of the diplomats behind the gates of the enclave. We entered through a heavy steel gate after a heavy-duty steel-barrier had been hydraulically lifted. Behind the gate was another gate just as large, the first gate closed and only then the second gate was opened (After a flimsy bomb-check of the underbody of the car with mirrors).

Inside the compound are several residential buildings, the embassy building itself and the british country club, with tennis courts and a bar. The place could not have been more cliché - WASPs playing tennis in white polo-shirts and matching white shorts, all of them looking very british. The barkeeper impeccably polite and deferent - and of course there was ale (In cans though). The whole setup would probably not have stood out too much in Europe (Just beeing identified as "typically british") - but seeing this whole setup right there in Pakistan, with all the dirt and poverty outside of Islamabad, it appeared bizarre.

After we had finally been able to submit our visa application for India (And having it setup to be sent to Lahore), we left the luxurios island that is Islamabad and headed towards Lahore, on the Grand Trunk Road.

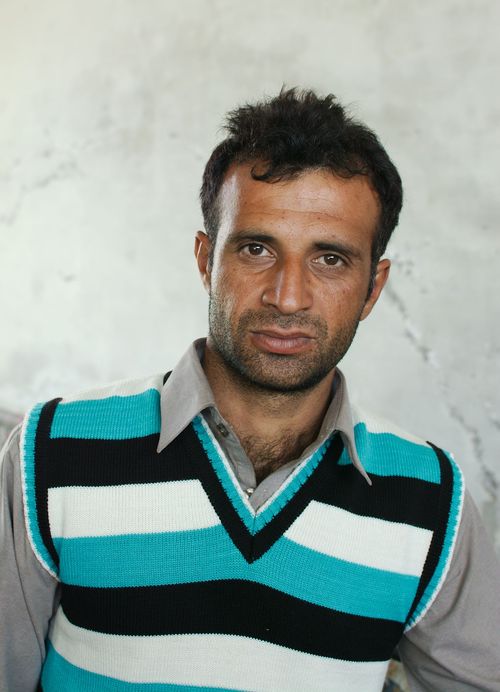

It is only 300km to Lahore, we arrived within 4 days (No police escort this time). The traffic had been ok in the beginning, but the closer we got to Lahore, the thicker it got. Most problematic though where the motorcyclists, who rode beside us for kilometers to interrogate us with the ever repeating questions of the where, why and how. It's not fun trying to concentrate on the erratic traffic while beeing pestered with questions by a guy who doesn't even leave you enough space to evade potholes and other road obstacles.

At some point, shortly before Gujranwala, we had accumulated two dozen motorcyclists, who found it incredibly entertaining to escort us along the road (And they probably thought we are some kind of celebrities or guiness book aspirants). We had already experienced how a crowd attracts an even bigger crowd in Iran, but this was getting out of hand. After an hour of this, we stopped to get rid of them, but they just stopped as well and bombarded us with even more questions (And there was always someone who hadn't picked up what we had already answered earlier, so it was just more of the same). So we continued, dragging along a crowd of male-only motorcyclists. Only when we stopped and Daniela went away to ask for the price of a hotel-room, they magically disappeared. Clearly i alone was not interesting enough to gawp at, lacking a female body and all.

Other than that, the Pakistani where incredibly respectful and friendly. On two of our three camping-spots on the GT Road we where quickly discovered by village people - and of course they didn't want us to sleep in the dangerous field we had chosen, inviting us to their home. Both times we talked our way out of their offer and where eventually left alone after dark (Only for them to come back in the morning to offer us food respectively an invitation to their house for breakfast).

I would have loved to explore the south of Pakistan, but we only had gotten a 2-month visa and we expected to soon get our India visa issued (And after all we wanted to be in Sri Lanka by spring, so we had to hurry - again).

In Gujranwala after a long search we found a scruffy hotel, but according to it's owner we had to register with the police first to be allowed to stay. So off we went to the police office in the dark.

There the low level officers didn't really know what to do with us and we waited for two hours (Sweaty, stinking, tired and hungry) till they reached someone higher up on the phone, who was willing to take responsibility of making the decision to let us stay for the night in Gujranwala. The officers where friendly and polite though, and they gave me a tour of the facility, including the prison and it's inhabitants.

On the next day we reached Lahore.

"The city of gardens" was supposed to be a nice place - a green city with beautiful old architecture and plenty of charming places to visit. It is not. Lahore is a moloch - i have never experienced such a noise level. The traffic is dominated by LPG-powered auto-rikshaws and the sound they emit is akin to a jackhammer - on top of that there's constant squeaky honking (Little did i know what awaited me on India's roads). Well, we would get our visa and quickly get out of there. While we where there, we made the best of it and did all the touristy stuff we where supposed to do (Badshahi Mosque, Shalimar Gardens, Minar-e-Pakistan, The Walled City, Wagah Border ceremony).

2 weeks later (4 weeks after we had submitted our visa application), christmas was close, the weather had turned from permanent mild and sunny to permanent cold, foggy and miserable, we where still waiting for the India visa.

Dozens of calls to the embassy hotline had been fruitless (Most of the time nobody picked up) and Gerry's visa dropbox (The courier service that handled all visa issues for the embassy) proofed to be useless and just told us to wait. When we finally had enough of beeing put off, i wrote a mail to the High Comission and we also asked the Austrian Embassy in Islamabad to intervene for us. A day later (The 21st of December) we got a call from Gerry's that our visa was ready for pickup. Incredible!

I'm not sure which of the two actions was pivotal (The mail to the High Commission or the invervention by the Austrians), but we received our first lesson on indian bureaucracy - nothing happens unless there's stern intervention!

The next day we picked up our passports and left. Unfortunately too late to meet Wagah border's closing time - and we had to stay in the desolate PTDC hotel at the border. Of all the rundown places we had stayed on this trip, this was in a class of it's own. Surely a state-of-the-art building in the 60s or 70s, no money had been spend on keeping up the infrastructure. Correspondingly the walls where rotting and black from mildew, the carpet was worn down to the backing layer and half of the windows where gone (Great ventilation!). The best part though - the room rate was 2000 Pakistan Rupees - 20$ - no bargaining. For the bargain we got a bucket shower - warmed up with an immersion heater, which the employees warned us not to touch while switched on.

Unterwegs auf der Grand Trunk Road und die Eindrücke der Städte

distance: 396.77km

duration: 47h 52min

Islamabad - GT Road - Lahore - Wagah Border

Die kalte Jahreszeit ist nun vorbei. In Islamabad scheint jeden Tag die Sonne bei ca. 25° Grad.

Glücklicherweise konnten wir über Warmshowers eine gute Unterkunft in Islamabad finden.

Ein toller Gastgeber, ein großes Haus, ein eigenes Schlafzimmer mit Badezimmer, ein Bett mit westlicher Matratze. Gekrönt wird der ganze Aufenthalt von einem Hauskoch, der uns jeden Tag Frühstück, Mittagessen und Abendessen kocht. Da ich mich unter diesen Umständen so gut entspannen kann, beschließt mein Körper mal für eine Woche so richtig krank zu sein.

Der Baugrund wird auch in den Nobelbezirken fast bis an den Rand der Grundstücksgrenze bebaut. Zwischen den aneinandergereihten Häusern bleibt somit nur ca. 2 m Abstand zum Nachbarn, gerade noch genügend Platz für einen Gehweg oder Parkplatz. In Österreich gibt es dafür Regeln.

Ich liege also krank im Bett und kann durch das Fenster gemütlich die Nachbarn auf deren Terrasse beobachten. So wie ich sie beobachte, haben auch sie mich schon längst krank im Bett entdeckt. Das Fenster in meinem Zimmer steht offen und die Nachbarin stellt sich so nah als möglich davor.

"Hello, are you sick? Can I help you? If you need some help, please tell me!".

Und so lernt man seine Nachbarn in Islamabad kennen.

Als wir am ersten Tag unserer Ankunft im F9 Park in Islamabad unsere Zeit vertrieben, wurden wir von einer Frau angesprochen. Sie war mir sehr sympathisch und wir tauschten Nummern aus.

Nachdem ich mich nach meiner Erholungspause wieder aufgerafft habe, bin ich mit meiner Bekanntschaft aus dem Park zum Einkaufen losgezogen.

Sie führt mich durch die beliebtesten Kleidergeschäfte und erzählt mir wie modebewusst die Frauen hier sind. Natürlich spricht sie vom oberen Viertel der Gesellschaft. Wenn die Kinder in der Schule sind und zu Hause keine Arbeit mehr ansteht, treffen sich die Frauen zum Kaffee oder zum Einkaufen.

Die Erziehung der Kinder wird sehr ernst genommen und auch das Vermitteln der Religion. Fünf mal beten am Tag ist angesagt. Mit Apps am Smartphone wird ihnen das Beten zu Hause erleichtert. Sogar das neue Smartphone, welches sich Christian in Pakistan gekauft hat, besitzt eine App fürs Beten, welche Suren aus dem Koran rezitiert.

Die Textilien werden in den Geschäften gekauft und dann zum Schneider gebracht. Jede Frau stellt sich ihre eigene Garderobe zusammen und somit sieht man kein Outfit ein zweites Mal.

In den darauffolgenden Tagen wurden wir mit der gesamten Familie zum Essen eingeladen und natürlich wurde uns stolz ihr neues Haus präsentiert.

Zu Besuch bei Familie Ahsan

Islamabad habe ich sehr angenehm empfunden. Es gibt sehr viele Grünflächen und Freiflächen. Die Strassen sind zwar sehr breit und dominant, aber der Verkehr teilt sich dadurch gut auf und macht auch das Radfahren unkompliziert. Die Stadt wurde 1960 auf dem Reißbrett entworfen. Jeder Sektor lebt von einem eigenen Marktplatz und eigenen Schulen. So ensteht etwas dörfliches Gefüge. Erfrischend sind die Margalla Hügel, angrenzend an die Stadt (geplant) ein beliebtes Naherholungsgebiet. Auch wir erkunden ein wenig die Berge.

Wir lernen das Leben von Expats in Islamabad kennen und können endlich wieder gutes, westliches Essen genießen.

Die Sicherheitsvorkehrungen für Expats werden sehr hoch geschraubt. Ein Besuch in der Enklave zeigt uns wie abgeschieden dieses Viertel lebt. Bei der Einfahrt wird der Motor abgestellt und das Auto wird rundherum vom Sicherheitspersonal kontrolliert. Wir erkunden den British Club und betreten eine völlig neue Welt. Man fühlt sich wie in einem Film, die Männer spielen Tennis und die Frauen trinken ihren Cocktail und sehen zu. Nebenbei gibt es Kindermädchen, die sich mit deren Kindern beschäftigen.

Einen besseren Platz könnte die Faisal Moschee in Islamabad nicht haben, zwischen Nobelbezirk und den Margalla Hills. Sie ist die größte Moschee Pakistans.

Schulen reisen mit Bussen an und neben der Moschee werden auch wir zu einer Attraktion ihres Ausfluges. Mütter wollen Fotos mit mir und deren Kindern. Die Schüler stellen sich einer nach dem anderen neben mich und fotografieren mit ihrem Smartphone.

Nachdem ich mich erholt habe und Christian das indische Visum beantragt hat, machen wir uns nach langem Aufenthalt auf den Weg nach Lahore auf der berühmten Grand Trunk Road.

Good Bye gemütliches Leben in Islamabad.

Die Eindrücke auf der Grand Trunk Road

Viel Verkehr, lästige Motorradfahrer, hupende Lastwagen, alles zusammen sehr anstrengend. Manchmal fühl ich mich geschmeichelt von alldem Ansturm, aber oft kann es ganz schön nerven.

Man kommt aber sehr schnell voran und wenn man es nicht eilig hat, sollte man hinter das Chaos sehen.

Biegt man von der Hauptstrasse ab, so wird es schnell ruhig und langsam. Die Leute sind alle ganz nett und bringen uns sogar Tee und Kekse an unser Zelt. Auf einem unserer Zeltplätze lernen wir die Besitzer des Grundstückes kennen und werden nächsten Morgen auf ein Frühstück eingeladen. Stolz wird uns ihr großes Haus präsentiert. Die jungen Männer gehen ins Ausland arbeiten, damit die Familie in Pakistan ein großes Haus bauen kann. Die gesamte Familie unter einem Dach. Jedes Pärchen besitzt ein eigenes großes Schlafzimmer. Auf jeder Etage eine Küche. Für Feste gibt es einen Speisesaal, es müssen ja alle einen Platz haben. Natürlich extra Gästezimmer mit je einem Badezimmer.

Repräsentation ist sehr wichtig, dafür wird im Ausland gearbeitet und man lässt die Mütter mit Kindern für Jahre alleine zu Hause.

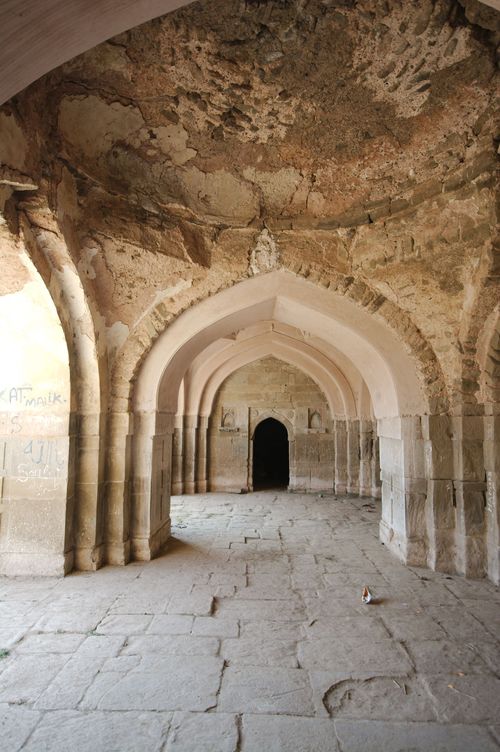

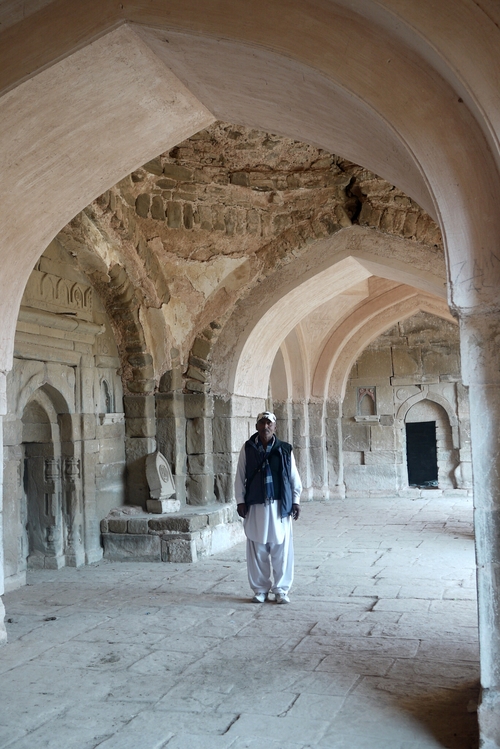

Wir kommen spät abends beim Rohtas Fort, einer alten Burgstadt an. Wir sollen laut den Einheimischen unbedingt in der 10 km entfernten Stadt schlafen, denn hier in diesem Dorf sei es zu gefährlich. Da wir nicht in der Nacht fahren möchten, entscheiden wir uns aber vor den Mauern der Burg zu campen. Kein gewöhnlicher Tourist bekommt so ein tolles Hotel mit interessanter Aussicht auf die Burg.

Es ist schwierig abzuwiegen, wann die Einheimischen die Wahrheit erzählen. Es ist laut Einheimischen immer und überall gefährlich. Wenn in Pakistan die Sonne untergeht, sieht man fast niemanden mehr zu Fuß auf der Strasse. Die Angst vor der Finsternis ist bei allen ein wenig zu spüren. Aber dieses Phänomen haben wir auch in den anderen Ländern schon erlebt.

Inmitten der Burganlage ist das alte Dorf noch bewohnt und belebt.

Wir werden im Burghof von pakistanischen Touristen angesprochen und bekommen ein Stück Geburtstagstorte angeboten.

Endlich haben wir die GT Road hinter uns gebracht und erreichen eine verstopfte, voll chaotische Stadt.

Willkommen in Lahore

Wir hoffen auf einen kurzen Aufenthalt in Lahore, denn die Stadt ist wiedermal nichts für Radfahrer. Wir suchen recht rasch unsere Unterkunft.

Das Hostel befindet sich neben einer stark befahrenen Strasse, am Dachboden. Es gibt drei schwindelige Zimmer mit Schiebefenstern, was soviel heißt: Lärm bei Tag und Nacht. Ich hab noch nie in so einem lauten und kleinen Zimmer geschlafen.

Wir hatten uns den Aufenthalt ein wenig anders vorgestellt. Wir warten und warten auf unser Indienvisum. Nach zwei verzweifelten Wochen (insgesamt 4 Wochen seit dem Antrag) noch immer keine Antwort. Anrufen ist nicht möglich, da keine Telefonnummer funktioniert. Persönlicher Kontakt zur Botschaft ist auch nicht erlaubt, es geschieht alles über eine Agentur. Auch unser Pakistanvisum endet eine Woche später und so werden wir richtig nervös.

Wir machten zum Glück schon Bekanntschaft mit der österreichischen Botschaft von Islamabad und so klopften wir dort verzweifelt an. Am nächsten Tag dann, endlich ein Anruf. In Islamabad wundert man sich über unsere Zweitpässe. Unsere Dringlichkeit wurde ihnen aber zum Glück von der österreichischen Botschaft nahegelegt und so erhalten wir in der vierten Woche in Islamabad unser Visum.

Neben dem vielen Warten haben wir uns auch Sehenswürdigkeiten angesehen. Zum Glück gab es was tun in der Stadt.

Die berühmten Gärten

Wir nutzen die Zeit und schicken unser Winteroutfit nach Haus. Was für ein schönes Postamt!

Und weil wir soviel Zeit haben, haben wir uns schon im Vorfeld die tägliche Zeremonie an der Grenze zu Indien angesehen. Es ist ein Wettkampf der Lautstärke zwischen Pakistan und Indien. Uns wird sofort bewusst welcher Staat größer ist, es dröhnt nur so von der indischen Seite her. Massen an Menschen, na da werden wir was erleben!

Die Wachablöse besteht aus einer Choreographie, einem großen Spektakel. Es ist ein militärisches Spiegelfechten, das symbolisch für den Konflikt zwischen Indien und Pakistan steht.

Als Abschluss von Pakistan durften wir dann im schönsten Hotel vor der Grenze übernachten. Eine Hotelkette der Regierung, 20$ haben sie uns abgeknöpft.